For the last few posts I’ve been focusing on describing what a bird looks like (specifically, plumage details). But to get a good, full description, there are several other aspects we must also pay attention to. These include:

- Behaviour

- Size & shape (perched and in flight)

- Vocalisations

- Habitat

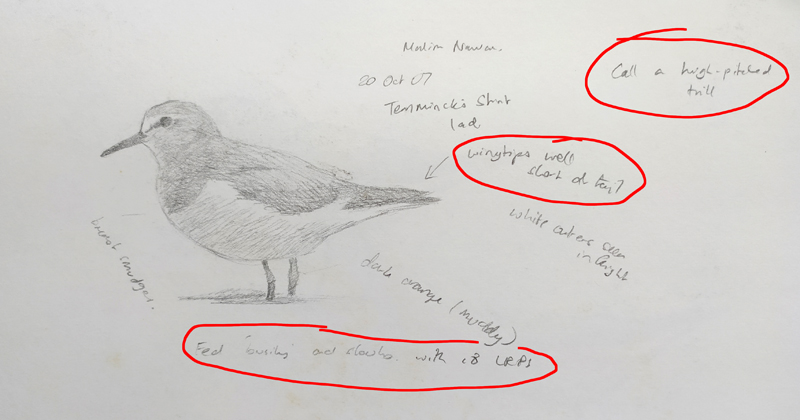

Behaviour: What is the bird doing (e.g. flying, foraging, etc)? Is it doing anything distinctive with its body (e.g. wings, tail, etc)? Is it calling or singing (see below)? Can its behaviour be compared to other species nearby (e.g. it feeds more actively or more sluggishly than x)? Does it appear to be shy or confiding?

Shape and size: Both shape and size are best described in comparison to something else. For example, “slimmer than a sparrow”, “longer-winged than a swallow”. Shape and size should be estimated ‘live’ rather than from still photos.

In different groups of species, there are certain parts of the bird to pay special attention to; for example, the primary projection in warblers (e.g. two thirds of the exposed tertial length), the length of the wings relative to the tail (e.g. slightly shorter than the tail), bill length (e.g. 1.5 x the head length) and leg length in waders; the wing shape in flying raptors, etc.

A word of caution about describing size. When viewing a single bird (or group of the same species), particularly in the absence of other ‘size referents’ (something of known size), it can be very difficult or impossible to make an accurate estimate of size. This is particularly true of a bird against the sky or sea. Even when there are other species present for direct comparison, ensure that you compare them when they are as close together as possible, and at similar distance from you. “Size illusion” is such a ‘big deal’ in birding that there have even been several scientific papers written about it. Here’s the seminal paper by Peter J Grant.

The posture and angle of the bird from the observer can also affect size perception, so it is important to check one’s first impressions. For example, this nightjar looks much larger than this one but they are both the same species. Because of the posture of the bird in the second photo (eye wide open, fluffed up), our mind can make the assumption that the bird is small, whereas, in the first, where the bird has pressed its feathers close to the body, it looks long and slender, and large.

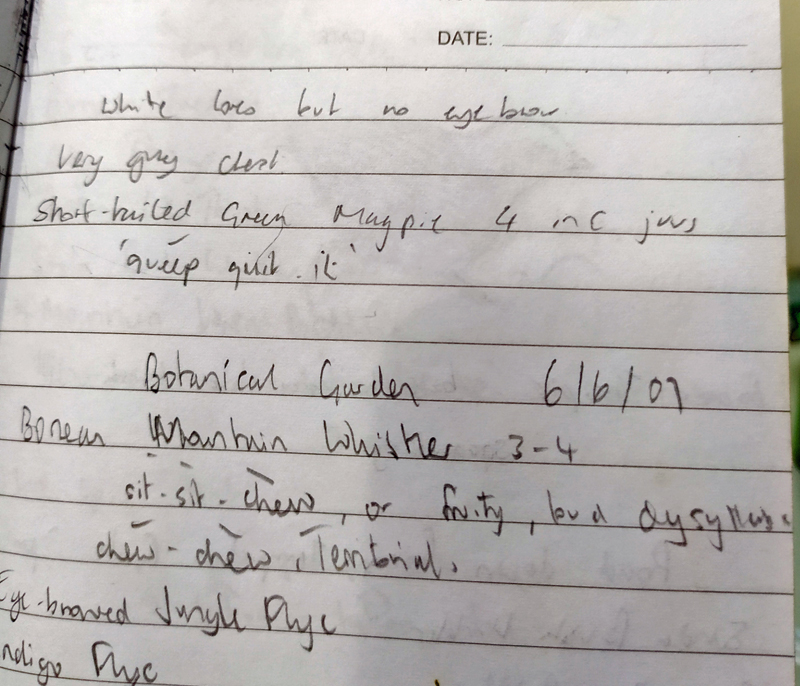

Vocalisations: Calls (contact calls, threat calls, alarm calls, flight calls, etc) tend to be short and simple; songs (generally but not always made on or near the breeding grounds) are usually more complex and ‘tuneful’. The simplest and best way to make a note of them is to record them on a device such as a sound recorder or a mobile phone. Failing that, it is possible to make written notes on vocalisations. One can use comparison (sounds similar to…), description (e.g. a musical trill, a series of staccato notes slowing and descending at the end, etc.), writing what the call sounds like (e.g. “cuckoo”, “ko-el”, “caw”, etc), or your own personal symbols to mimic the sound.

Habitat: Where a bird is found is a very important aspect of identification. Both the macro-habitat type (e.g. montane mossy forest, mangroves bordering rivermouth, etc.) and the micro-habitat (in the canopy, in tangled undergrowth near the ground, etc.) should be noted.

Practice!

- Write down a description of differences in size, shape and behaviour of the two species in this video.

- Write a description of the vocalisations of the bird in this video.

I’ve been lurking and enjoying this series – “back to basics” and useful for all.

Thanks John. Lurkers welcome!